Players, coaches and commentators often talk about ‘taking time away’ in a tennis match – the ability to starve opponents of the necessary milliseconds to cover the court and strike the ball cleanly. It’s a phenomenon anyone who has picked up a tennis racquet will recognise, but one that has never been quantified – until now.

Tennis Australia’s Game Insight Group has introduced a new stat to discuss the phenomenon in real terms. Time pressure – the average time a player takes away from his or her opponent on each shot – is one way a player can dictate a rally and is strongly associated with winning the point.

So how do players generate time pressure? It’s not simply a case of hitting the ball harder, explains GIG’s Dr Machar Reid, Head of Innovation at Tennis Australia.

“If you just look at ball speed, that doesn’t take into account where you’re standing on the court,” he explains. “Take Rafael Nadal – he often parks himself way back from the baseline, but he cranks the ball. Then there’s someone else, like a Bernard Tomic, who might be further up the court but doesn’t generate anything like the ball speed. What you’re feeling as an opponent is quite a bit different.”

Those differences are borne out in the top five ‘pressure makers’, those players identified by GIG as the best at applying time pressure. Subtract the time taken for a player’s ball to reach the net from the time taken by their opponent’s ball, and you have a player’s time pressure. A positive time represents a player successfully taking time away from their opponent; players with a negative number are the ones feeling time pressure.

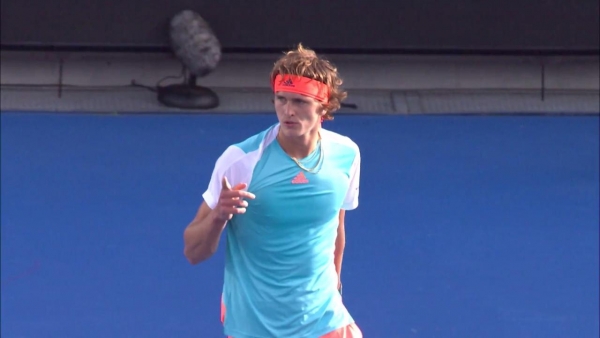

“The two factors you are really looking at are contact point with the ball – in essence, how close you are to the baseline or net – and the speed they put on the ball. For example, among the men’s top five Cilic and Pouille are not necessarily heavy hitters with large amounts of spin, their strokes typically have a very flat trajectory which allows it to come through the court quickly. But they’re also trying to hold their position on the baseline as best they can. In contrast, Zverev is typically set further back from the baseline, but hits with higher ball speed.”

Of course, if tennis was simply about time pressure, all players would simply step closer to the baseline and hit harder. There are other ways to beat an opponent independent of taking time away.

“Time pressure doesn’t take into account the effect of the ball when it hits the court,” adds Reid. “When you think about Rafa’s steepling bounce off the court, that’s placing you in a really uncomfortable position in terms of you contact point, so you’re less likely to get as much purchase on the ball.

“We’re also not touching on where the ball is being directed. Some players will direct it closer to the lines than others, some players will mix things up and use their shot-making to create space – Roger Federer and Ash Barty, for example.”

Nevertheless, time pressure is an important part of the story of how tennis matches are won and lost, one that is now quantifiable and comparable in real time.