This article first appeared in the June/July 2022 issue of Australian Tennis Magazine, one of the world’s longest-running tennis publications. For more in-depth features, news and analysis, you can subscribe now.

At the highest level of tennis, the difference between the best and the rest is often the smallest of margins.

Many stars have adjusted their styles or approaches, under different coaching or in search of an edge that allows them to take the next step as an athlete.

Some, like Maria Sharapova, have had to adjust their playing style in the aftermath of a major injury, while others needed to conquer one surface or in some cases, one opponent.

Daria Saville recently revealed a suite of technical changes linked to several of the above factors.

RELATED - Shape, heaviness and forehand-dominance: the evolution of women’s tennis

Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andre Agassi are among others who’ve changed their styles – be it minor or major – in search of that extra advantage.

Saville’s changes became clear after her recent return from injury. Having missed the best part of two years with Achilles’ pain – which had plagued her for even longer than that period – the 28-year-old adjusted her court position, serve and backhand grip.

The changes have paid off, with a rejuvenated Saville registering wins over Ons Jabeur, Elise Mertens and Petra Kvitova – among others – this year. Improving her ranking from outside the top 600 to the verge of the top 100 within three months, the Australian is naturally trusting her game.

“(I) found my level sooner (than expected) and I’m winning, so I’m like, ‘Okay, well let’s work’,” she commented after a third-round appearance at Roland Garros. “I just work with what I have, and I guess I’m playing well.”

Switching hands

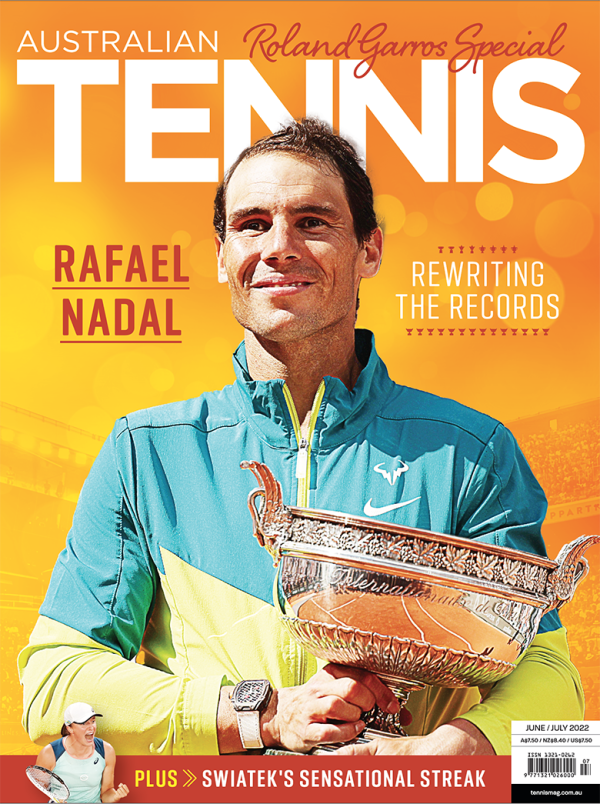

Far earlier in his tennis journey, Nadal arguably made the most significant change of all. The 22-time Grand Slam champion is widely considered the greatest left-handed player in tennis history. But the quirky thing is that tennis is the only activity in his life that he does left-handed, with the Spaniard born as a naturally right-side dominant person.

Nadal recently discussed the phenomenon when talking about his love of golf. “I’m a little bit strange in all of that. I eat and play basketball with the right (hand). I play tennis with the left,” he said. “I started playing golf when I was at the age of 17 or 18, and naturally I started playing with my right hand.”

How he came to play left-handed was almost by accident. It's often said that his long-time coach and uncle, Toni Nadal, wanted him to hold an advantage over his opponents by creating a point of difference, but he has rejected that claim.

“No! That’s a legend,” Toni once explained in an interview with US Tennis Magazine. “It’s really not the truth. At the start, he played with two hands but using one hand to direct.

“I had the impression that he was stronger on his left side than on his right side. So, I figured that he was left-handed; it’s as simple as that.

“I did advise Rafa that at the age of 10, he needed to stop playing his forehand with two hands because no top player had a two-handed forehand and I couldn’t imagine my nephew being the first.”

Toni insisted there was nothing more to the story. “Would Rafa be as strong now if he used his right hand?” he said. “That’s something we don’t know, and we will never know.”

Retired Japanese star Kimiko Date did the exact opposite. Born a natural left-hander, she reached world No.4 after training herself to utilise her right hand for tennis.

“When I was young, everything I did – writing, eating, my parents tried to change me using my left hand to doing it with my right hand,” she explained.

“You see, when we (in Japan) are writing on paper, we write from the right-hand side at the top, not from left to right like they do in the west. That’s why we need to always use the right hand.

“When I started playing tennis at six years old, I always followed my parents and so I picked up the racquet and started watching other people and just copied them.”

Some changes in playing style are more subtle than switching hands, as Roger Federer demonstrated after employing longtime idol Stefan Edberg as his coach in 2014 and 2015.

Federer won 11 ATP titles in that period, and while he didn’t win a major in that time, Edberg helped revitalise a career that had earlier appeared to be in decline. The primary focus was a more attacking mindset, which was the catalyst for Federer’s return to Grand Slam glory in 2017 and 2018. A predominately serve and volley style was one of the key features that had been a cornerstone of Edberg’s own career.

“If you do not move forward, eventually the other guy will do it and find their way into the point and then you’re going to be struggling,” Federer said at the time. “And in defence you can only get out of defence that many times.”

Federer’s average rally length has dropped to 3.5 shots per point since the start of 2016, which ranks sixth among all players in that time.

Backhand execution

Federer’s majestic single-handed backhand remained his standout feature. Dominic Thiem, the 2020 US Open champion, is widely admired for the same stroke. But the weapon was far from natural for the Austrian, despite it being one of the most effective strokes in the game.

“It was actually the decision of my coach because I was 11 years old when I switched,” Thiem said after his US Open triumph.

“I put so many hours of work into it because probably my more natural shot is the two-handed backhand, that’s why I started with it. I guess a kid starts to play the backhand how it feels natural to him or her.

“So this is not as natural as many people think it is. It’s a well-worked shot.”

Germany’s Tatjana Maria made the same change but much later in life.

Maria took a tour sabbatical after the birth of her first child in 2013, and under the guidance of her husband and coach Charles Maria, she returned to the tour with a single-handed backhand.

“I was before playing a lot of slice and my husband told me when I was pregnant, let’s try (to) change your backhand,” Maria explained ahead of the Hobart International in 2016.

“It’s not easy, but I’m really happy we did it,” she said of her new backhand style. “I was working really hard on it and it’s getting better every day. Now it feels normal.”

Aesthetics were at the heart of a similar decision for French teenager Diane Parry, who stunned defending champion Barbora Krejcikova in the first round at Roland Garros. The Parisian-based 19-year-old grew up admiring former world No.1 Amelie Mauresmo, prompting her transition to a single-handed stroke at age 13.

“It’s Amelie Mauresmo that taught me,” said Parry after winning the first match of her major main draw debut at Roland Garros in 2019. “I love it. I’m very happy to have a one-handed backhand. I’m one of the very few players to have one, so I stand out thanks to this.”

Serving style

For other players, like Sharapova, major style changes are born of necessity. The former world No.1's serve was considered one of her greatest playing attributes when she burst onto the scene in the early 2000s, helping Sharapova claim three Grand Slam titles between 2004 and 2008.

Chronic shoulder pain and eventual surgery led to Sharapova streamlining her action, and a more compact, balanced position. Early in her career, Sharapova typically rotated her shoulders in front of her hips, which provided additional leverage but also contributed to her eventual shoulder breakdown. By the end of her time on tour, Sharapova’s hip and shoulder were more aligned and she was driving through the legs instead of relying on an unnatural twist.

Djokovic was also compelled to make changes to his serve after his comeback from an elbow injury in 2018.

Working with coaches Andre Agassi (who required a similar overhaul) and Radek Stepanek, the Serbian refined his service motion to improve the technique and, as Djokovic explained, “release the load from the elbow, obviously something that I have to do because I have the injury.”

In a similar way to Sharapova, Djokovic’s focus now is on a more compact swing. “It’s not entirely different, but at the beginning, even those small tweaks and changes have made a lot of difference mentally,” he explained. “I needed time to kind of get used to that change, understand whether that’s good or not good for me.”

Agassi modified his own service motion because of an injury in his career and he helped shape that change which still exists today.

“Both Radek and Andre have discussed a lot before the information came across to me,” Djokovic said. “They spent a lot of hours analysing my serve. I did, too.”

Plenty of players have been forced to change their technique through injury, others have done so in their quest to gain a little bit more from their game or even for pure enjoyment. Regardless of the circumstance or reasoning, many competitors have found that change itself can be a valuable weapon.