The full version of this article first appeared in the August/September 2023 issue of Australian Tennis Magazine, one of the world’s longest-running tennis publications. For more in-depth features, news and analysis, you can subscribe now.

August 2023 marks 50 years since computer rankings. Romanian Ilie Nastase made history as the first No.1, atop the inaugural ATP list of 23 August 1973. Ironically, the showman known as ‘Nasty’ wasn’t a fan of the newfangled official pecking order, believing the cold, hard numbers and pursuit of higher rungs had a chilling effect on player relations.

“I didn’t really have much time to enjoy my top ranking when I had it, because everybody wanted to take it away from me,” Nastase reflected 40 years later, of his 40 weeks at the top.

It’s a refrain from many former No.1s. Enjoyment of the feat is greater in retrospect, partly because the prestige of being numero uno has grown immeasurably over the decades.

Nothing has impacted the game more than computerised rankings, with the arguable exception of tennis going professional in 1968. It’s no exaggeration to say rankings rule the game, and the lives of players. Rankings determine which tournaments players enter, whether they are seeded, or whether they steel themselves for the rigours of qualifying. Aspiring pros literally go to the ends of the earth in pursuit of a precious ranking point.

Rankings before rankings

Given the modern obsession with computer rankings, it’s hard to overstate what a groundbreaker the system was in its day. Even the concept of an official No.1 didn’t exist prior to computer rankings.

Year-end subjective rankings lists, compiled by tennis writers, broadcasters, ex-players and national associations, named their season No.1s and top 10s. But there was no consensus. Creation of computer rankings allowed the players to define No.1 as a new universal measure of greatness, alongside the majors.

The ATP itself was uncertain of how ‘official No.1’ would be accepted. Fans were accustomed to hailing Grand Slam champions as the game’s greats; for many, the Wimbledon winner was de facto world champion. How meaningful was a No.1 ranking in April or August? And players on the computer could ascend to No.1 anywhere. Nastase’s historic feat came in the off-Broadway locale of South Orange, New Jersey. The top ranking could even fall to a player without taking the court – via the loss of a rival in a faraway event.

The game took some time to warm to computer rankings. The rolling, 52-week report card on the players wasn’t as thrilling or convincing as a stadium-shaking Grand Slam victory. Newspapers, magazines and other pundits continued to issue their annual rankings lists. The International Tennis Federation still names its official world champions, giving more weight to majors; its 2022 men’s No.1 was Novak Djokovic, not top-ranked Carlos Alcaraz.

But the No.1 ranking has emerged as one of the ultimate prizes in tennis, an end in itself rather than a byproduct of a Grand Slam title. The pursuit of No.1, once almost an afterthought, is the overarching narrative in the game.

From snail mail to live rankings

No one had any inkling in the freewheeling 1970s that computer rankings would become so ubiquitous and influential. Tennis was ahead of the curve – golf didn’t produce official world rankings for men until 1986 and unbelievably for women not until 2006. But the ranking system in those pioneering days was far from a slick operation.

Doubles rankings didn’t arrive until 1976, women’s rankings were inaugurated in 1975 and ATP rankings weren’t issued weekly until 1979. In the early years, they were published at irregular intervals, sometimes six weeks apart.

The ATP didn’t even own the computer that produced the rankings. In the mid-70s, ATP employees would take the reams of player statistics to a nearby Los Angeles aerospace company, to run through their mainframe. The rankings would be delivered on gigantic sheets of computer paper, to be pasted up in the ATP office and distributed at circuit events around the world.

Up to the mid-1980s, before fax and internet, the rankings were published in the ATP newspaper, International Tennis Weekly, and delivered via snail mail. A far cry from today’s digital data smorgasbord, with up-to-the-minute live rankings and every conceivable stat at every fan’s fingertips.

Rankings as player power

Computer rankings sprang from the dawn of the Open era and its rising tide of player power. Early pros were agitating for more control over their careers, with the formation of the player union Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) in 1972 and the ATP boycott of Wimbledon in 1973. The rankings system, created by the players for the players, was another bold leap into the professional era – and a blow to the crumbling old amateur power structure.

ATP rankings imposed a professional, merit-based criteria to ensure players were treated equally and fairly across the game’s competing fiefdoms. For the first time, everyone was singing from the same hymn sheet, or ranking list. Tournaments no longer invited players; they accepted them if they made the entry cut-off.

While the rankings today are all about celebrating No.1, the impetus for the rankings was more about figuring out who was No.28 or 56 or 100. Computer rankings were devised as the official form guide for determining tournament entry and seedings.

Prior to computer rankings, national associations and tournament committees decided their player fields, often giving preference to local names and draw cards. Players would write to tournament organisers weeks or months in advance, asking for an invitation to compete in their events. With the advent of official rankings, player livelihoods would no longer be at the whim of tournament organisers.

Discretionary power was still afforded to tournaments in the form of wildcards, and some slots were allotted for qualifying. But the bulk of the player field would enter the draw based on their ranking.

As well as giving players more autonomy over their careers, the ranking system enabled the ATP (and later WTA) to wrest more control of the game from national associations and amateur officials.

No perfect system

Today’s rankings system is unrecognisable from the first iteration. The history of tinkering, tweaking and redesign of the rankings highlights that there’s no perfect system. Every regime has had its proponents and critics, its anomalies and flaws.

Whatever the methodology, the ranking system has to strike a credible balance between quality and quantity; between recognising the Grand Slams as the tentpoles of the sport, and rewarding week-in, week-out consistency at ATP events where the majority of players earn their livelihood. It must reward champions while giving incentive to underdogs to climb the ladder, without skewing in favour of one group at the expense of another.

ATP rankings in the 1970s and 1980s used the average system. Tournament points accrued (increasing in number with every round) were divided by the number of tournaments played, with a minimum divisor of 12.

Players couldn’t simply overtake higher-ranked foes by playing more events. The more tournaments, the greater the divisor. Workhorses felt penalised by the average system, with its diminishing returns for increased play.

Another feature of this system was bonus points, awarded for wins over players ranked in the top 150 (with a top-five scalp worth 30 points). So, while tournament points were awarded for how deep a player went in an event, bonus points recognised the calibre of opponent. Semifinalists at the same event might each receive four different points totals, depending on the rankings of opponents they beat.

Bonus points were universally loathed by top players, who felt they added a bounty to their heads, in addition to the pressure of defending their hefty points from the biggest events.

An anomaly of the average system was that it could reward players for competing less. A career-high ranking could be attained while out injured or on holiday. In 1986, for instance, French hero Yannick Noah missed Wimbledon with injury and rose to a career-best No.3. Instead of a divisor of 17, his points total was divided by 16, boosting his average and allowing him to overtake 18-year-old Boris Becker, who defended his Wimbledon title but received no ranking reward, stuck at No.4.

For top players, whose consistency ensured high averages from relatively lean schedules, there was a disincentive to play more and risk diluting their average. As a result, the superstars were lured to big-money exhibitions.

The advent of the ATP Tour in 1990 aimed at rectifying these flaws by getting players to compete more often on effectively their own circuit – the ATP Tour being a partnership between players and tournament directors.

Through the 1990s, ATP rankings used a ‘Best-14’ system. The points average was scrapped, along with bonus points, in favor of a higher required number of events – 14 instead of 12 – with the sweetener that only 14 events would count. Players could discard poor results at any event. The more they played, the more they could cherry-pick what went towards their points tally.

Howls of protest ensued. “We’re the only sport where every game doesn’t count,” said long-time No.1 Ivan Lendl in 1992. “You should not be allowed to have 15 lousy results and they don’t count because you have 14 better ones.”

The system had tipped too far towards quantity over quality. And the ATP Tour overplayed its hand by diminishing the Grand Slams, which did not have to count a jot in a player’s ranking. In 1990, Stefan Edberg was the year-end No.1 despite losing first round at both the French and US Opens. Can you have a ranking system that doesn’t count majors?

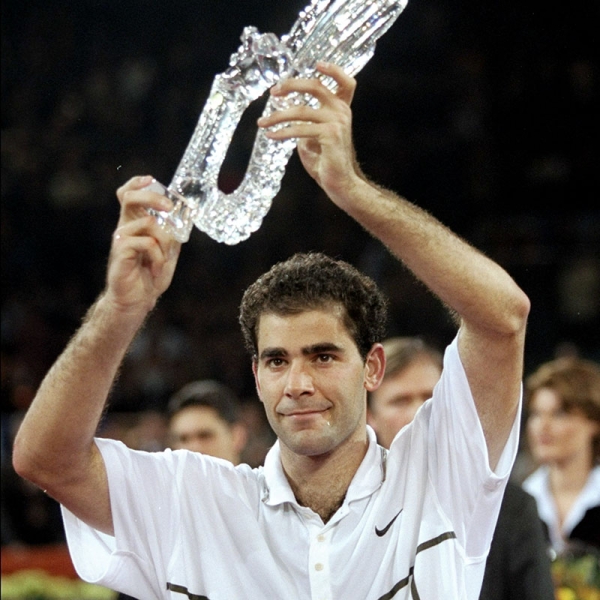

The most scathing criticism came from top players. “Just because you’re No.1 on the computer, doesn’t mean you’re the best player in the world,” taunted Pete Sampras, the season-ending No.1 for a record six consecutive years (1993-98).

“To me, the ranking system is like giving a professional golfer mulligans,” said fellow No.1 Andre Agassi. “They could hit a bad shot and say, ‘You know what? Let’s just not count that one. But we will count it if you hit a better one.’”

The Best-14 system also enabled surface specialists to shark up the bulk of their ranking points on their preferred courts. In early 1996, Thomas Muster ascended to No.1 on the strength of his clay fiefdom. The Austrian strongman won 12 events in 1995, 11 of them on clay.

“I feel that Thomas is the best player in the world on clay,” Sampras told the Los Angeles Times. “As far as him being the best player … I don’t quite swallow that.”

Stung by the criticism from fellow No.1s, Muster protested: “This is the system … it’s not like I’m buying the points at a supermarket.”

Two years on, in March 1998, that system propelled Marcelo Rios to No.1. The first South American atop the rankings, the Chilean is also the only No.1 without a major title.

The new millennium brought a radical rethink. Believing fans were confused by the rolling 52-week rankings, the ATP promoted the Champions Race as the new ranking system in 2000. Players started the year on zero points – like Formula One – and amassed points through the season, before No.1 was crowned at year’s end.

Only problem was, the Champions Race couldn’t determine tournament entry cut-offs and seedings. The former rankings were still required for this purpose. Rebranded the Tournament Entry System and buried from public view, it existed as a shadow ranking system.

No one was fooled as to the ‘real’ rankings. Lleyton Hewitt, leader of the Race in early 2000, didn’t consider himself No.1 and nor did anyone else. The flinty Aussie eventually reached the summit as season-ending No.1 in 2001, as the US Open and Masters champion.

The ATP swapped one confusion for another. Fans wondered why Hewitt, as No.1 in the Champions Race, was not seeded No.1 at tournaments. The race format also deprived the game of the excitement of hailing a new No.1 mid-season.

The race experiment felt like an overreaction to season 1999, the most crowded at the top, when five men – Sampras, Carlos Moya, Yevgeny Kafelnikov, Agassi and Patrick Rafter – ruled at No.1. Riveting alpha-male showdown or revolving door in the penthouse? The Best-14 system had cheapened the feat of reaching No.1. If the top ranking can change hands eight times in a season, is it such a singular achievement?

At the same time, in reforms to the Entry Ranking System, the ATP moved to correct the quantity-over-quality bias and also give the Grand Slams their due by compulsory inclusion of results from the majors and Masters series in a Mandatory 13. A ‘best five’ component remained as incentive for more play in smaller events.

This remains essentially the ranking system today, with a ‘best seven’ component extending the total events counted to 19 (20 for the elite eight who contest the ATP Finals). So, while not every result counts, all the top-level events do.

Even with the disruption of the pandemic, and Wimbledon being stripped of rankings points in 2022 over the exclusion of Russian and Belarusian players, the current system enjoys a greater level of acceptance than ever before.

The No.1 who wasn't

For the greatest ranking credibility crisis – or epic fail – see the sad saga of Guillermo Vilas. On every measure but the ATP rankings, the Argentine icon was No.1 in 1977.

The soulful, top-spinning ‘Poet of the Pampas’ was the only multiple major winner – at Paris and New York (the last year the US Open was played on green clay) – and runner-up at the Australian Open on Kooyong grass.

The attritional left-hander compiled all-time records that still stand: most titles in a season (16), most match wins in a season (136) and longest winning streak in the Open era (46 matches).

Despite a banner year that would rate alongside any No.1, Vilas ended 1977 at No.2, behind Jimmy Connors, his victim in the US Open final. The average system punished Vilas for his Herculean schedule. Connors topped the rankings with zero majors and eight titles, half the record haul of Vilas.

“I was winning and winning and could never take the next step to No.1,” a visibly affected Vilas rued in 2017. “The system did not help me at all.”

In 2014, Argentine tennis journalist Eduardo Puppo and Australian-based mathematician Marian Ciulpan campaigned to have Vilas retrospectively recognised as No.1 by the ATP. (The drama is the subject of the Netflix documentary Guillermo Vilas: Settling the Score.)

The twist? Painstaking analysis of tournament and rankings statistics across the 1973-78 seasons led to their conclusion that Vilas would have ranked No.1 not in 1977 but in September-October 1975, and again in early 1976, if rankings had been issued in those weeks.

The Vilas petition drew inspiration from a similar ranking saga involving Evonne Goolagong Cawley. In 2007, the WTA acknowledged that the Aussie would have been No.1 for two weeks in 1976, had official rankings been produced weekly, as they are today. WTA history was amended and Goolagong Cawley awarded her place in the No.1 honour roll, 31 years after the fact.

Alas for Vilas, the ATP did not follow suit. While then-CEO Chris Kermode acknowledged the enormous effort and emotional toll that went into the campaign, the ATP did not want to open a Pandora’s Box of future claims from players arguing for latter-day recognition of their ‘real’ career peak. Although Vilas is probably the only player who could mount a case for retrospective No.1 status, the ATP chose not to make an exception for him.

“It’s a huge deal for a player, so we haven’t taken this lightly at all,” Kermode explained in May 2015, having taken months to pore over the Vilas case. “We just can’t adopt this version of rankings as official history. I feel 100 per cent confident (that) rewriting history is impossible.”

Final proof, if it were needed, that the ranking system can be as ruthless as any opponent. Both career-maker and heartbreaker.

Carlos Alcaraz, the ATP's newest world No.1, is the cover star of the August/September 2023 issue of Australian Tennis Magazine.