Thirty years ago, Monica Seles returned to Australia — the place she loved most — carrying scars that no champion should ever have to bear.

She loved visiting Melbourne's iconic zoo, where she would make a beeline for the koala enclosure. She loved shopping in the CBD, the support of the crowds, and the ease of accessing practice courts compared to other Grand Slams.

Seles loved riding her bike from her rented house to Melbourne Park, where the brilliant left-hander had never lost a match entering the Australian Open 1996.

Centre Court — now known as Rod Laver Arena — was her personal playground.

But during a 28-month absence from the sport, following her horrific stabbing by a deranged fan in Hamburg in April 1993, Seles couldn’t even stomach the sight of a tennis court.

She would walk to the edge, stare at it, think about stepping inside the lines, then retreat.

“The tennis court had been my domain,” Seles wrote in her autobiography Monica: From Fear To Victory. “There, I was invincible and untouchable. When (attacker) stabbed me, he took all that away.”

The physical injury took a matter of weeks to heal. The psychological damage was far more taxing.

Seles, justifiably, slid into an abyss of fear, anxiety and depression during her hiatus, before finally returning to the tour in late 1995, and to Australia the following January — unbelievably, three decades ago now.

Boris Becker had also been somewhat on the outer entering 1996.

The German powerhouse hadn’t stopped playing, of course, but it had been five years since he had won a major — the Australian Open 1991. He also had not won a solitary match in Melbourne in three years.

At the ripe age of 28 — yes, that was considered ‘old’ in 1996; Becker was actually a few months younger then than countryman Alexander Zverev is now — it appeared “Boom Boom” had been permanently usurped by Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi.

Becker’s long-time rival Stefan Edberg played his 13th and last Australian Open after announcing 1996 would be his final year on the tour.

Edberg partnered Petr Korda — the father of Sebastian Korda — to take out the men’s doubles, but the popular Swede bowed out of the singles in the second round, two days before his 30th birthday, losing to little-known Frenchman Jean-Philippe Fleurian, who was already 30.

"It felt good in one way, bad in another way," Edberg said of the crowd's cheers as he departed.

Mark Woodforde and Todd Woodbridge — the iconic “Woodies” — surprisingly bombed out in the opening round of the doubles, falling to fellow Aussies Josh Eagle and Andrew Florent.

Woodbridge made the third round of the singles, where his run was halted in an 8-6 fifth set by American ace Jim Courier. Three decades later, the pair are still involved, behind the microphone for Channel 9.

Woodforde, older still than Becker and Edberg, went on the greatest singles surge of his life, becoming the first Aussie since Pat Cash (1988) to reach an Australian Open semifinal.

There, the South Australian southpaw's magical run ended at Becker's brutal hands, in three lopsided sets.

“I think Boris had one of those days where probably God could have been at the other end, and he (Becker) still would have beaten him (God) pretty easily,” Woodforde shrugged.

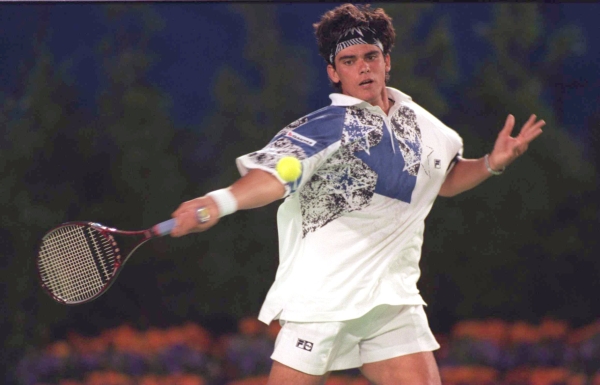

Woodforde conceded six games across three sets himself when he brought 19-year-old Mark Philippoussis back to earth with a splat in the fourth round.

Two nights earlier, “Scud” fired 29 aces and 65 winners in a stunning three-set dismissal of Sampras in one of the most hyped, electric third-round clashes in the tournament’s long history.

“In the end he (Philippoussis) was basically serving aces at will,” then Davis Cup captain John Newcombe remarked.

The then tournament director Paul McNamee had taken the unusual step of announcing at lunchtime Friday before that Sampras-Philippoussis would be the feature attraction Saturday evening, the match regarded as the birth of the floodlit blockbuster.

“Tonight was like nothing else I have felt before,” Philippoussis said. “I felt I couldn't do anything wrong on serve.”

Sampras’ shock defeat saw Agassi, the reigning Australian Open champion, take over as world No.1.

Agassi took some time to get going in 1996, before finding his groove when he came from two sets to love down to beat Courier.

It was Agassi’s first victory over Courier since 1990, launching him into a semifinal stoush with yet another American, Michael Chang.

Chang prevailed in three sets, which, apparently, is precisely what Agassi wanted, the Las Vegan desperate to avoid facing Becker, who he had fallen out with in 1995.

“I know I can win, but I also know that I will lose,” Agassi claimed in his autobiography Open. “In fact I want to lose, I must lose, because Becker is waiting in the final. The last thing I need right now is another holy war with Becker. I couldn’t handle that.”

Chang, who now coaches Australian Open quarterfinalist Learner Tien, had not dropped a set all tournament in 1996. But Becker was a tall order. The German was taller, too, than the 175cm Chang.

“When we walked onto the court to start the match, we stood together at the net for the ceremonial photos prior to the coin toss,” Chang wrote in his autobiography Holding Serve: Persevering On And Off The Court.

“I looked over at Boris, who stood 6-foot-3. I decided to have a little fun. I stood on my tippy toes while the cameras clicked away. Boris noticed what everyone was grinning about, so he stood on his toes.”

Becker wasn’t head and shoulders better than Chang in the decider, but he was superior, triumphant in four sets to snap a five-year famine with his sixth and final major.

“To tell you the truth, I didn’t think I had a Grand Slam left in me,” Boris admitted to the sell-out crowd during his victory speech.

Comeback queen Seles, meanwhile, almost came unstuck in the semis through a combination of a sore left shoulder and the bruising forehand of American Chandra Rubin, who is in Melbourne this week behind the mic.

Rubin was showing no signs of fatigue after outlasting Arantxa Sanchez Vicario — the pair would go on to win the women’s doubles together — 16-14 in an epic third set in their quarterfinal marathon.

PODCAST: Listen to Chanda Rubin on The Sit-Down

No fifth-set breakers in those days. You played until you flaked.

Another marathon was looming when Seles found herself behind for the first time all fortnight.

“‘Get back in the game, Monica’, I told myself after losing the first set,” Seles said. “And I did.”

After levelling in the second set, Seles again trailed Rubin in the third, 2-5, before peeling off five straight games to reach the final.

There, she faced a powerful, blonde German — not Steffi Graf, though, sidelined following foot surgery.

Anke Huber advanced to her sole Slam decider and broke Seles early.

But she was soon snowed under by Seles’ raw double-fisted power on both wings, the match swiftly descending into a no-contest.

Later that night, Seles went to a nightclub and danced with Huber, the pair joined by Mary Joe Fernandez.

Seles was just 22 when she collected her ninth Slam, 30 years ago. Like Becker, she never won another one.

But in that moment, it didn’t matter.

“Originally, I wanted to win to prove something to myself,” Seles said. “Then, when the press kept reporting that I was going to win, I wanted to win to prove them right.

"But in the end it was about going onto a court and playing great tennis.

“That’s what I missed most when my world was more darkness than light, and I realise now that it’s not something anyone can take away from me.”