The public view of the medical team in Melbourne is of on-court treatment - the crowd watching on, holding a collective breath.

After several tense moments assessments are made, limbs manipulated, advice given. The player nods and gets to their feet. The crowd exhales. They’re ok.

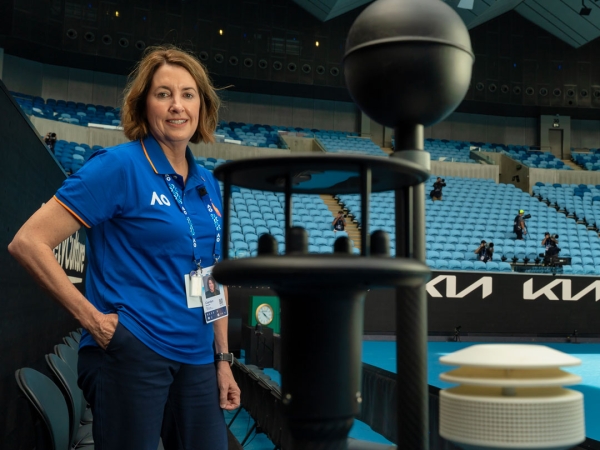

The medical team are a huge part of what keeps the Australian Open running smoothly. They’re always at the ready to swoop in when injury strikes, but – as Chief Medical Officer Carolyn Broderick explains – there is so much more that goes on behind the scenes.

“I think what most people see about what we do in player medical is our court calls,” Broderick said. “But that’s just a tiny fragment of what we do.”

“We also are cognisant of the fact that players are touring the world for 11 months of the year now. So, things we take for granted like getting our skin checked, getting our vaccinations, getting pap smears, all that sort of thing, we want to try and offer to players here.”

During the Australian Open, you’ll find Broderick and the team in the pop-up player medical centre, tending not only to injuries and infections, but also specialist issues that require dermatologists, optometrists and podiatrists on site. The centre is open every day from 8am until an hour after the final match is called.

One of the health advances Broderick is most proud of during her time as Chief Medical Officer is the development and implementation of the Australian Open Heat Stress Scale.

“2018 was my first AO,” she explained. “It was very hot, and I realised that we really needed a heat policy that was based on good science. So, we started collaborating with the University of Sydney with Professor Ollie Jay, who’s a world expert in thermophysiology.

“We developed a Heat Stress Scale that took into account not just environmental parameters, which is what happens in most sports, but also the important things that are happening with most players.”

This covers the internal metabolic heat produced as a result of exercising, the clothes players are wearing, and how easily they can evaporate sweat. This sophisticated algorithm takes away any subjectivity, resulting in a more accurate reading.

“We’ve got the Heat Stress Scale on display in all the player areas - in the locker rooms, training rooms, dining room, so that the players not only know what the heat stress scale is now and what might happen, but they can see the forecast … I love the fact that it’s so transparent.”

Not only have these guidelines proved invaluable for the Australian Open, but now with the development of a freely available online tool, this advice has also been adopted by school and sports medicine communities.

“What it takes into account [of] is the actual activity that the person is doing in the hot environment, which has been missed in previous sports policy,” Broderick said. “So, a person who's playing lawn bowls in a hot environment is going to have a different risk of exertional heat illness compared to someone who's running a marathon in that same environment.

“The exciting thing about it is we've got a fabulous data scientist there at the University of Sydney, who's downloaded all the postcodes in the world and so it's now going to have a worldwide experience.”

The Heat Stress Scale is just one way a player is able to ready themselves for their match at AO 2026. Ahead of the tournament, Carolyn’s team also sent out advice around what they could do to prepare in the lead-up to their time on court.

“Acclimatisation is the most effective personal tool for preventing your risk of exertional heat illness,” Broderick said.

“To fully acclimatise it takes between 10 and 14 days. That’s why we are noticing that our players are coming out here much earlier … We're encouraging [them] that [it’s] not only enough just to sit in the heat. You need to be training in the heat to acclimatise, but that can make a big difference.”

To add to the challenge, not all heat behaves the same way, and that’s something that Broderick and her team have considered. “Traditionally [we have] a dry heat in Melbourne,” she said. “[It’s] hot, very hot, but dry, whereas a number of the other tournaments in the US and in Asia that are impacted are not so hot in terms of temperature, but a lot of humidity.

“It's about adapting to our type of heat to where we know the radiant heat is higher, but the humidity is less, and there's advantages of that and different ways of coping with that.”

This year, with Broderick’s Heat Stress Scale well and truly implemented, the tournament’s Chief Medical Officer is looking forward to making further strides in sports medicine.

“I'm always excited leading into the AO, but I think from a medical perspective, I'm excited about our new offerings … the mental health workshop and our fertility clinic. And I’m excited [because] it’s almost a new era in tennis,” she said.