Milos Raonic, Grigor Dimitrov, Kei Nishikori: in some ways they are the forgotten generation, the lost boys of tennis. They were at the leading edge of the new wave of players who arrived to threaten the Federers, Nadals, Djokovics and Murrays of this world when they turned pro in 2007 and 2008.

And of that generation, Raonic is the most lost of all. It is not that he has not had his moments in the sun – he reached the semifinals in Melbourne in 2016, and six months later faced Murray in the Wimbledon final – but it is just that every time he has been in a position to make his move, to establish himself as a true contender, another part of his body has broken down and his chance has been whipped away from his racquet strings.

Nishikori is in much the same boat (one Grand Slam final reached, a whole heap of injuries endured) but he has managed to maintain his role as a seriously challenging nuisance for the big boys as they home in on the silverware. Raonic has seldom been healthy enough for long enough to get that far. As for Dimitrov, he has, at least, won the ATP Tour Finals, so he has a big trophy to polish and gloat over at home. But other than that, he has little to show for his many years on the road.

For many players, the constant round of injury, rehab, inching back up the rankings, another injury, more rehab and more time off would have broken their spirit. Maybe their DNA was trying to tell them something. But not Raonic: he has taken each setback in his inordinately long stride (he stands 196cm, and most of it is leg) and come back older, wiser and even more determined to make the most of his moment when it came.

Now into his fourth Melbourne quarterfinal (the Australian Open is his most consistently successful Grand Slam), Raonic believes he is playing well, competing well (he has had a nightmare draw of Nick Kyrgios in the first round, Stan Wawrinka in the second and Sascha Zverev in the fourth) and – for the moment, at least – he is healthy and moving well. Now Lucas Pouille is the only obstacle between him and the last four.

“I had a really good off-season,” he said. “I put in some of the best hours in a long period of time, maybe if ever. I'm not the kind of guy that needs a lot of matches.

“For me, it's about being sharp, moving well, and being efficient with my serve and this kind of thing. If I can get those kind of things, my serve always buys me time in matches and in tournaments to sort of figure things out. It can keep me alive for a while.

“As long as I have the freedom to put in the work and with no physical hindrances, I think I can always give myself a chance.”

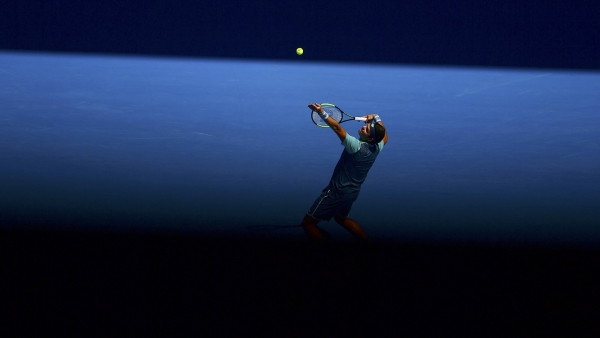

Raonic has been meticulous in his approach to his career. The walloping serve has always been the bedrock of his game but bit by bit, season by season, he has worked on every other aspect of his arsenal to recreate himself as the complete player. With a serve like that, why not volley behind it? Because while he knew what to do at the net, he didn’t know how to get there. So, work on the backhand to turn it into both a useful tool to create a point and a real weapon.

Slowly, slowly the technical bits and pieces were put in place, but still there was the biggest problem of all: that grey stuff between the ears. Raonic has rather too much of it. He is bright, is Milos, but sometimes he is too bright for his own good. If he reacts spontaneously to a situation on court, his sheer power can be devastating. But if he has time to think, he can tie himself up in knots. And if he starts to get down on himself as a result of the knot-tying thing, he can be on his way home.

But even on this, Raonic is working behind the scenes. He knows his own strengths but he also knows all about his weaknesses – and his mid-match mental state needs constant monitoring. In Brisbane, he lost a match he should have won against Daniil Medvedev, and he was not happy. But with analysis, thought and a change of heart, he thinks he might have solved the problem.

“It was all really emotional and mental,” he said. “I believe I had eight break chances in those first two sets against him. I had more than enough opportunities to make the most of it and that can go a completely different way.

“But then I got a little bit too down on myself, and I think that sort of shined a light on something that I really have to do differently at this event. And I think I have worked on that, and I think I have also had to play against top players where I couldn't afford to be undisciplined in that regard.”

And then there is Goran Ivanisevic, who started working with Raonic in March of last year. Goran is from Croatia, Milos is originally from Montenegro – they share a common language and heritage. Until Goran won Wimbledon in 2001, he was regarded as the man who was clearly good but who could never make it count at the major events. Three Wimbledon finals; three confidence-shattering losses. No, Goran would never win a big one. But he did – and then he showed Marin Cilic how to win the US Open in 2014. Now he is trying to work his magic with Raonic and, so far, the big man seems to be thriving on it.

If he can stay injury-free and positive in his outlook, Raonic may yet remind the world that the class of 2008 is not finished yet.